Tax News You Can Use | The Northern Trust Institute

Jane G. Ditelberg, Chief Tax Strategist

February 9, 2026

Under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the gift, estate and generation skipping transfer (GST) tax exclusion went up to $15 million per individual and $30 million per married couple as of January 1, 2026. Even taxpayers that used up all their existing unified credit in previous years now have an additional $1.1 million tax exclusion and can expect to have more in the coming years as the current number is indexed for future inflation. While some taxpayers see this as a sign that they will not need to worry about transfer tax planning, others are seeing the opportunity to harness the power of lifetime gifts.

The Low Hanging Fruit

Every U.S. taxpayer can make gifts of up to $19,000 per individual ($38,000 per married couple) to as many individuals as they wish each year without gift tax consequences. Each $19,000 gift saves $7,600 in estate tax for a donor with a taxable estate, even without any income or appreciation on the assets. Consistently making annual exclusion gifts is a powerful way to move assets out of a taxpayer’s taxable estate.

Example 1:

Harper and Sam, a married couple, make 30 years of annual exclusion gifts to one individual. Not accounting for any increase in the size of the annual exclusion, investment return or inflation, this would move over $1.14 million in today’s dollars out of their taxable estates, resulting in over $450,000 in federal estate taxes avoided. If Harper and Sam make gifts to four individuals each year, they will have moved $4.5 million out of their estates and saved over $1.8 million in estate tax.

Not every gift qualifies for the annual exclusion. Gifts that qualify include outright gifts to individuals, gifts through the Uniform Gifts to Minors Act, gifts using 529 plans, and gifts to a limited group of specific trust types. In addition, if the recipient is a grandchild or other skip person (more than two generations younger than the donor), then the gift also has to be coordinated with the GST tax annual exclusion rules, which are slightly different than those for the gift tax annual exclusion.

The Power of Early

A significant advantage of lifetime gifts is the opportunity to transfer any future appreciation of an asset to your chosen donee without any transfer tax cost. If the value of the asset appreciates between the time of the gift and the time of the donor’s death, the appreciation is in the hands of the beneficiary — not the decedent — and it avoids estate tax. While this estate tax savings can be speculative, as values are not guaranteed to rise, the tax savings can be significant, even if it must be balanced against the loss of the step-up in basis at death.

This applies to annual exclusion gifts discussed, to gifts that use the taxpayer’s gift/estate/GST exemption and to taxable gifts as well.

Example 2:

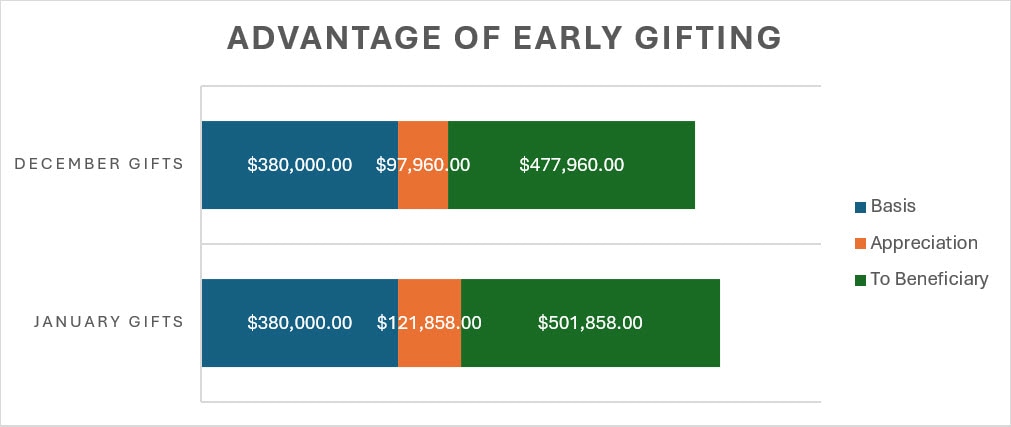

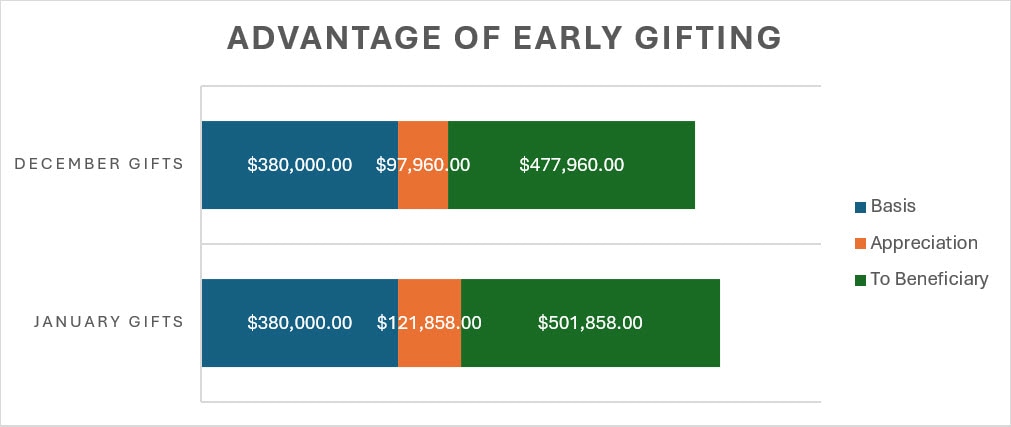

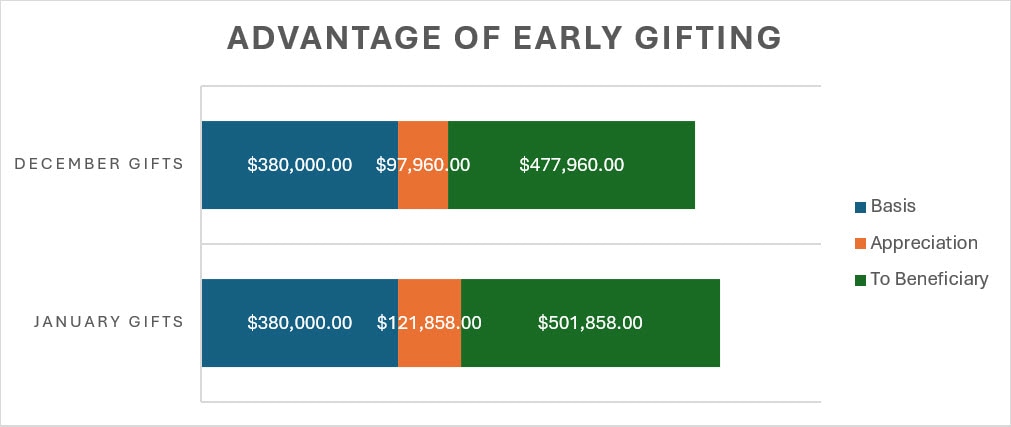

Chris and Pat are a married couple with one child. If they made gifts of $38,000 (annual exclusion for a couple) to their child at the beginning of each year for ten years (a total of $380,000), then, assuming a 5% annual pre-tax total return, the value of those assets at the end of year 10 would be over $501,800. None of those assets would be subject to estate tax, saving over $200,000 in tax.

Now suppose Chris and Pat also made $38,000 in gifts annually for ten years to four grandchildren and five nieces and nephews. This would be a total of $3,800,000 in gifts that, with appreciation, would be valued just over $5,018,000 at the end of ten years. This avoids over $2 million in federal estate tax.

Recognizing that the appreciation enhances the tax savings, it matters when a taxpayer makes gifts. The new annual exclusion is available on January 1 of each new year. Many taxpayers lose out on a year’s appreciation by waiting until the end of the calendar year to make these gifts. If we look at Chris and Pat’s gifts again, we can compare the benefits of making the gift on January 1 of each year with making the gift on December 31 of each year.

Over time, that additional year of appreciation adds up, so waiting until year-end may not lead to the optimal tax result.

Bigger Gifts, Bigger Benefits

As we saw above, making even small gifts of appreciating assets can have a significant tax impact over time. Lifetime gifts in excess of the annual exclusion are subject to the gift tax, but each taxpayer has an exemption (currently $15 million per person or $30 million for a married couple) that can be applied to eliminate any tax due. Making larger lifetime gifts can make sense when a taxpayer has rapidly appreciating assets, sufficient financial stability to afford the gift, and a long enough time horizon where the benefit of owing no estate tax on the assets given will outweigh the loss of the step up in basis that would happen if the taxpayer held the asset until death (or the possibility that the recipient will retain rather than sell the asset so the basis will not be an issue).

Example 3:

John purchased 10,000 shares of Microsoft stock in 2012 when the share price was $23.60, and he immediately made a gift of the shares (worth $236,000) to his daughter Sarah. John died in 2025 when the share price was $468 and the shares were worth $4,680,000 in the aggregate. In making that lifetime gift to Sarah, he transferred $4,444,000 (the growth in value from $236,000 to $4,680,000) out of his estate without paying any transfer tax. Assuming that John has a taxable estate, the estate tax savings is $1,777,600. This is offset against the $1,057,672 in income tax that Sarah would incur if, upon John’s death, she sold the stock with John’s original cost basis of $236,000, assuming a 23.8% combined capital gains and NIIT tax. This nets a total tax savings of $719,928.

The Power of Leverage

For those taxpayers who may have relatively little gift/estate/GST tax exemption remaining, lifetime gifts may still make sense. If making a gift using exemption is good, then making a gift that uses less exemption than the transferred property may be worth is even better. This involves using estate planning techniques that leverage the amount of remaining exemption to get enhanced benefits.

- One way to make a leveraged gift is to make a gift of property that can be valued with a discount. For example, giving an undivided fractional interest in a parcel of real estate (e.g., ¼ of a parcel rather than 2 out of 8 acres) is something that valuation experts (and courts) agree is worth less than a simple fraction of the fair market value of the whole property. This is because the recipient would need to have the property partitioned (typically a judicial action) to be able to sell only their part, which makes it harder to extract value from the gift. This means that a gift of a one-tenth fractional interest in a parcel of real estate valued as a whole at $1 million might be valued at, say, $85,000 instead of $100,000.

- A larger discount may be available if what is transferred is an interest in a private business entity, where extracting value for the shares received would be even more challenging. If a business owner gives 10% of the shares of a closely-held business with a going concern value of $100 million, the gift tax value may be more in the range of $6 million instead of 10% of the going concern value (which would be $10 million) since the recipient will have an interest without a ready market and without a sufficient vote in the business to influence distributions or liquidations.

- If the appreciation is all the taxpayer wants to give away, then a grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT) may be appealing. With a GRAT, the donor retains the right to receive an annuity from the trust, with whatever is left at the end of a term of years going to the donee. It is possible to set the value of the annuity close to the value of the assets, such that very little exemption is used to transfer all the appreciation to the intended beneficiaries. If the property does not appreciate, it is all paid back to the grantor in the annuity payments, so the grantor is not worse off than if they had not made a gift.

- Other leveraging techniques include:

A bargain sale — Selling to the beneficiary for less than fair market value, where only the reduction in value is a gift.

A net gift — A donee agrees to reimburse the donor for the gift tax owed on the gift, which reduces the value of the gift.

A split interest trust — Splitting the gift between a charitable and a non-charitable beneficiary, where only the interest of the non-charitable beneficiary is a taxable gift.

Tax Inclusive vs. Tax Exclusive Transfers

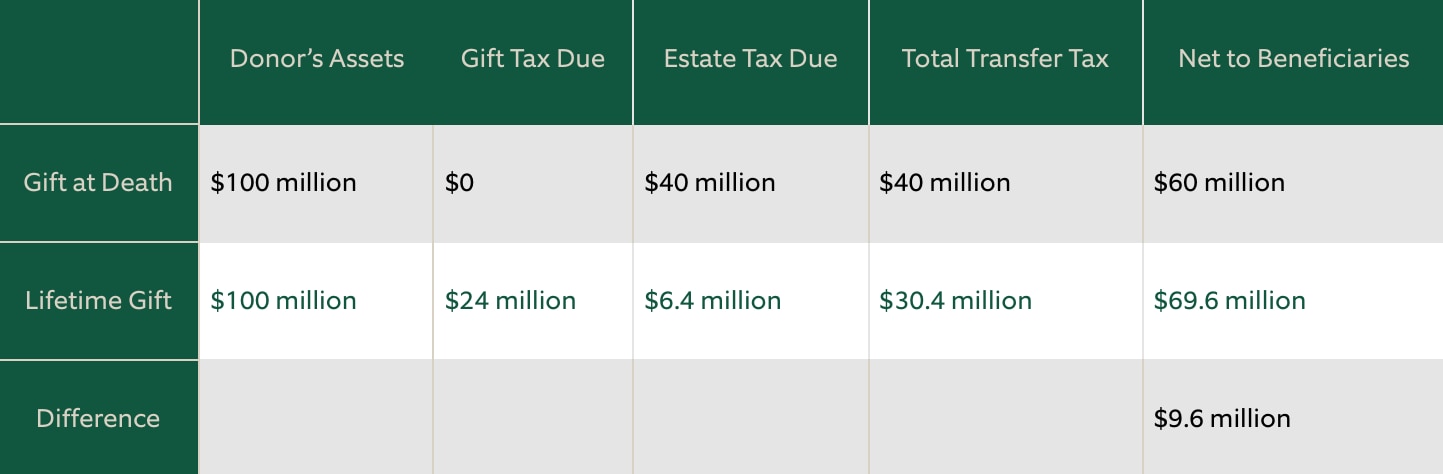

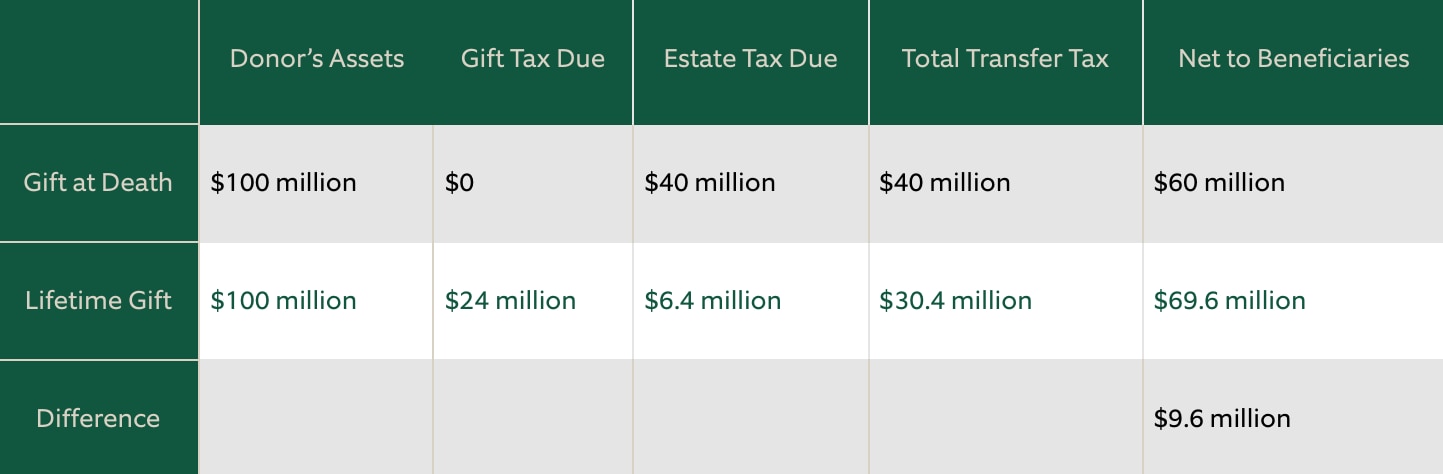

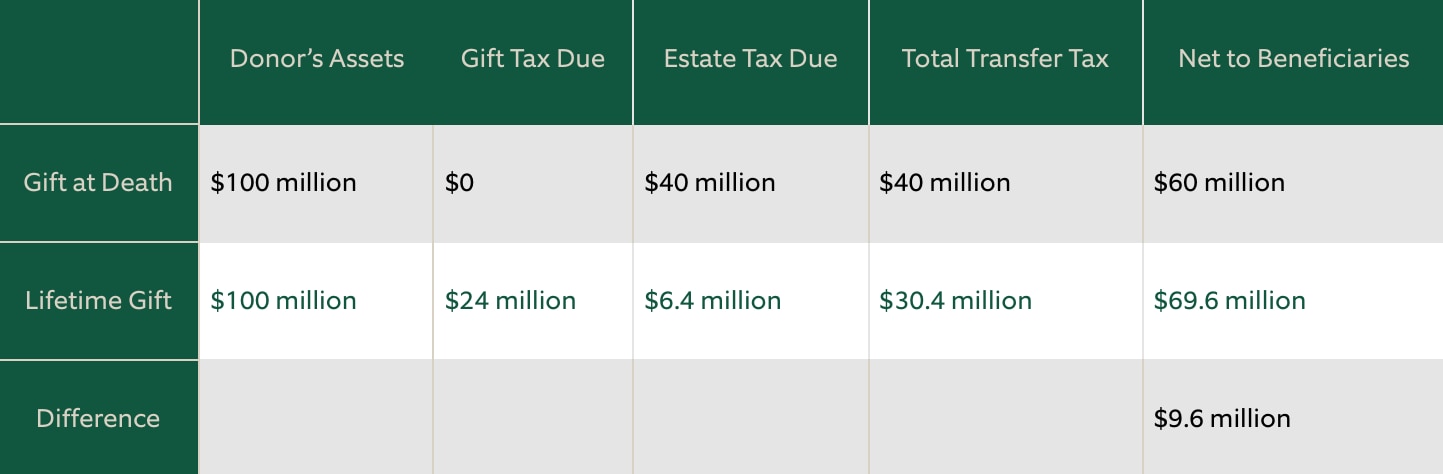

For those considering gifts that would go beyond their exemption and generate a gift tax, it is important to know the difference between how the tax is computed for lifetime gifts and for transfers at death. The estate tax is imposed on all the assets owned by the decedent on the date of death. While there are deductions for gifts to spouses and charities and for the amounts of taxes, debts, and expenses that the estate must pay, there is importantly NOT a deduction for the dollars used to pay the estate tax. This means that if the decedent dies having used up all their exemption with an estate valued at $100 million, there will be estate tax due of $40 million, and the beneficiaries will receive $60 million. The $40 million in tax includes tax on the $60 million going to the beneficiaries and tax on the $40 million going to the IRS. This is known as a “tax-inclusive” calculation.

Now, for the donor to make a gift of $60 million during life, the tax would be 40% of $60 million, or $24 million. This $24 million would be out of the donor’s estate and not subject to gift or estate tax. If the donor had a $100 million estate to begin with, there would still be $16 million left over in the estate at death, and an additional $6,400,000 in estate tax would be due, leaving the beneficiaries with an additional $9,600,000.

There is one caveat to keep in mind when making gifts that generate gift tax. Because of this difference, there is a catch if the donor makes the gifts too close to their date of death. The tax on gifts made within three years of the date of death is brought back into the estate and taxed at death as if it had not been used to pay the gift tax.

In addition, if these were low-basis assets, there would be a loss of the step-up in basis when assets are transferred during life instead of at death. However, if gift tax is paid, the amount of the tax is added to the basis, which will reduce potential future capital gains tax. This needs to be considered in evaluating the potential tax savings.